Without Bitterness

“...you can suffer injustice and you can still go on to live your life without bitterness or resentment.”

The Subjects

In the early 1900’s Tomiyo and Ryukichi Morita left Japan shortly after their arranged marriage and took a boat to the United States. They settled in southern California and worked first as farmers, then as hotel owners in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo. After leaving the hotel business, Ryukichi started a successful landscaping company alongside his wife, Tomiyo, who raised seedlings in their backyard. The Moritas settled into their lives in the United States and had five children. When Pearl Harbor was bombed and the United States declared war against Japan, the youngest of the Morita’s children was already in high school. Shortly after the war began, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which sent 120,000 Japanese-American citizens into incarceration camps in isolated areas of Colorado, Oklahoma, Eastern California, Idaho, Wyoming, Arizona, and Arkansas. The Moritas were forced to abandon their home, business, and all of their possessions. They were incarcerated in Camp Amache in southeast Colorado, where they were held for three years, until the war’s end. Fumiko—their youngest daughter— graduated from high school in the camp. Her older sister, Yayeko, worked at the camp’s unofficial newspaper.

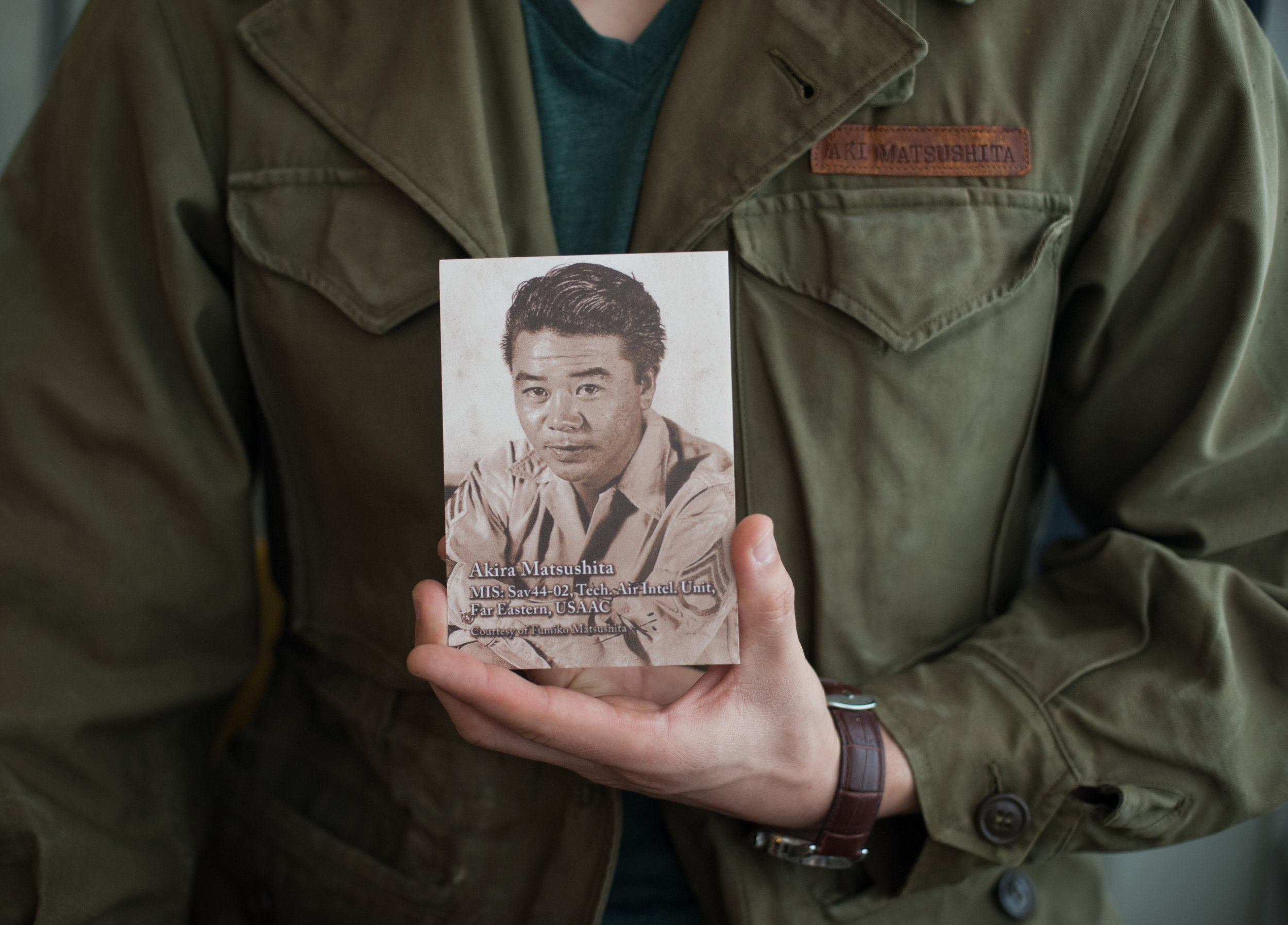

During the same period, another family—the Matsushitas—also farmers in southern California, were incarcerated in Arizona’s Gila River Camp. While in the camp, their son, Akira, enlisted in the US Army. He served in the Military Intelligence Service, a unit where many Nisei (second-generation Japanese-Americans) served as translators and interpreters, and assisted in interrogations.

When war ended and they were released, both the Moritas and Matsushitas moved to Chicago, Illinois. There, at a Japanese-American community basketball event, Akira—the former US soldier—met Fumiko, the Morita’s youngest daughter. They married and settled in Chicago, where Akira worked developing photographs at Peter Pan Portrait Studio. They had two children: Elaine and Kevin.

Neither Fumiko nor Akira spoke about their experiences during the war. Only when their daughter, Elaine, began asking questions did her mother reveal more about her incarceration under Order 9066. Elaine became a journalist and worked at several prominent newspapers including Chicago Tribune and Miami Herald. She has two sons, Josh (26) and Sam (22), and continues to live near her mother, Fumiko, and her aunt, Yayeko. The two sisters have lived in the same apartment building for 59 years and spend each day together. Akira, Elaine’s father, passed away in 2002. In 2010, he was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal for his service in the war. In 2016, Fumiko, Elaine, and her son Sam made a pilgrimage to the site of Camp Amache, where Fumiko and her family were held. In June 2017, Elaine’s oldest son, Josh, joined a trip sponsored by the Japanese American Citizens League and visited Manzanar, a former incarceration camp outside of Los Angeles.

Below is their family story as told by Elaine, Sam, and Josh, and through the heirlooms they hold dear.

The Heirlooms

Sam's "9066" Tattoo

“…the one [tattoo] that I’ve had the longest is the Executive Order number 9066…I didn’t really know a lot about that story and my grandma and grandpa’s family history…until I was probably in middle school. I had to do a class project…and I think it involved interviewing a family member, and so I interviewed my grandma…and that was when I first learned…about it…It gave me a lot stronger of a sense of who my family is, who I am.”

Elaine and her mother, Fumiko.

“I’m 3rd generation Japanese American. My grandparents on both sides were the people who came to the states from Japan…My mother was in high school when war broke out and they went into the camps. I’m going to say she was like sixteen or seventeen in 1942.

…they could only take one suitcase each. They had to leave their homes and were sent to Santa Anita race track, which was an assembly center where they were held until the camps had barracks built. So they lived in horse stalls at the racetrack. And then they were put on trains when the camps were ready. They were put in trains and the shades were drawn so they didn’t know where they were going. And I believe she told us that it took four days by train to get from California to this eastern Colorado location where the camp was. So for four days they were on this train. They couldn’t see anything. They didn’t know where they were going or what would happen when they got there.”

“60% of the population that was interned was American, born in this country, many [were] kids. They took orphans. They took elderly. They took people’s homes [away from them]…it wasn’t by choice that these people were there. They lost their rights.”

Sam's Guard Tower Tattoo

“That one was based off of a picture I took last May. My mom, my grandmother and my uncle went…on a pilgrimage to the area where the camp was located that my grandma was actually interned at. So it’s [based off of] a picture I took of the guard tower there...”

“It was surrounded by barbed wire fences. There were guard towers there with armed military in them. And I don’t know how many barracks were in this camp, but there were 7000 people [incarcerated there].”

Guard Tower at Camp Amache, 2016. Photo Courtesy of Elaine.

“There’s this raw, natural beauty broken up by barbed wire…it was nice for me to be able to…see where we could have been if we were born 35 years earlier. To see where our country is headed if we start making registries of people and fearing people. It was enlightening and heart wrenching and educational.”

“…neither of my parents or my aunts and uncles, they never talked about camp. And it’s not surprising because…kind of embedded in Japanese culture is this word ‘gaman’…it’s just: grit your teeth keep going. So I think that’s why they didn’t talk about it. I mean, you just grit your teeth and keep going. You don’t look back. You just keep going.”

Family Photos of Pilgrimage to Camp Amache

“The one barrack that they had rebuilt there was the exact same one that she [Fumiko, Sam’s grandmother] had stayed in…We were standing inside that building and she was telling us about her family living in there.”

The reconstructed barracks where Fumiko and her family were incarcerated for 3 years, 2016. Photo courtesy of Elaine.

“They had reconstructed one barrack that we could walk through so I could see the size of the space [that] my mother’s family was in. At the time there were only five of them…three children and my grandparents living in…I don’t know how big the space was but it was very small…they were there for three years before the war ended.”

“They did have school. They went to school there. And I was just reading recently too: there were a lot of the internees [that] served in the camp police, camp fire department. They served in the mess halls, in the hospital. They had a newspaper. My aunt worked at the newspaper. My mom worked at the hospital. My mom graduated in the camp from high school.”

“She [Fumiko, Elaine’s mother] used to go on annual visits [to Camp Amache] with some of her friends. It doesn’t seem to be something that causes her distress or sadness. I think if anything it’s…[Elaine takes a long pause] maybe I’m projecting because this is what it represents to me, but it’s paying tribute to her parents, her past, and what they endured and survived. Paying tribute to that.”

Fumiko pays tribute at Camp Amache with her daughter Elaine (behind her) and grandson Sam (right), 2016. Photo courtesy of Elaine.

“And one thing that we’ve learned is that the camp experience was so different for people depending on their age. Like, young children—real young children—they were taken care of just like children are, you know? For the high school age kids… I think there was something good in having this community around you all the time. But for my mother’s parents’ generation? We never got to talk to them about it, but it must have been incredibly horrific. They left their homeland to come some place for opportunity. They were getting the opportunity and trying to establish these lives here as immigrants, which wasn’t easy but they were doing that. And then it was all taken away: their homes, their properties, their belongings, were all taken away and they were sent off to these camps…”

Akira's Army Jacket

“My dad’s family when the war broke out were sent to a camp in…Arizona about thirty miles southeast of Phoenix…My dad, while his family was in camp…volunteered to serve in the [US] Army. My dad served in the Military Intelligence Service…that unit did translation and interpretation and interrogation for the US Army.”

Josh (26) wearing his grandfather's US Army jacket.

Official US Army Photograph of Akira

Josh, wearing his grandfather's US Army jacket and holding his grandfather's US Army photo.

“He never did [talk about his service in the military]. Once we were visiting a relative in Montana…shortly before my dad died. And my cousin’s husband got my dad talking about it [his military service] and he heard this great story from my dad that I’d never heard…when my dad was in the service and he was in this room with these other US soldiers, and he was doing translation but it just so happened that he was armed and the other soldiers weren’t. And he found…irony in that that. He was this Japanese guy in the US Army and he was the only one with a weapon in that room.”

“My grandpa was really quiet. Things I remember about him…he used to pick us up after school sometimes. I remember coming home with him one day and there was a new fort [playground] in the backyard. He would take us to judo. We would go to judo like three times a week and he would take us every day.”

Akira's Gi

““[This] Was my father’s gi. My father was a black belt in judo…And he took my brother to learn; my brother got a black belt. And that was my dad’s gi, and the kanji on it, that’s my dad’s name.”

Congressional Gold Medal

“…the gold medal with the soldier on it is actually the Congressional Medal. And it was designed specifically for the Japanese-American veterans of WW2…there were three groups that the Japanese-Americans served for the US Army…one was the 442 Battalion, and they were one of the most decorated combat teams in the US Army. There was also the 100th Infantry Battalion. And then my dad served in the Military Intelligence Service…And all three of those groups in 2010…were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal. My mom and I went to Washington to receive the medal for my dad who had already passed…My dad passed in 2002.”

The Golden Crane

“I don’t know if you know the story of Sadako and the 1000 cranes? It’s kind of a children’s book, but the story is about the origami cranes [that] are considered good luck. And in Hiroshima, where the bomb was dropped during WW2, people are always stringing the 1000 cranes and taking them to the memorial there…and some people for a grand occasion, make the cranes and then turn [them] into art. So that framed artwork is actually made up of 1000 folded origami cranes…laid over each other to form another form of art. And we had that made for my parents’ 50th wedding anniversary. So all the relatives…folded and folded and folded all of these [golden] cranes and we had an artist put them together to make that work…it’s something people do to express their good wishes for someone.”

Family Photograph: Akira, Fumiko, 2-Year-Old Elaine

“That was taken in the apartment that my mother still lives in...After the war…most of my childhood he [Akira, Elaine’s dad] worked at a baby photography studio called Peter Pan Studio and he processed film there. He didn’t…he wasn’t the photographer. I know another Japanese-American man my dad’s age who also was in photography and…I’ve heard stories where the company didn’t want them to shoot [photographs] because they didn’t want them dealing with the public. They wanted them in the back…

So my parents arrived in Chicago because [they] couldn’t get work in California. After the war there was still so much prejudice. So they came out here. [To the Midwest.] They heard you could get hired here. And I only mention that [about the photography studio] because even though they could get hired, there obviously was still prejudice.”

“After the war the West Coast didn’t really want Japanese Americans. Some returned to LA and were able to find jobs but to leave camp...you needed to have a employment, to be...offered a job somewhere, and most people went towards the Midwest. And my uncle was given a job—my grandma’s brother—and so then the whole family moved out after he had gotten a job and was able to get housing for them. And they’ve lived in the same building ever since. It’s pretty amazing.”

Fumiko & Yayeko's Apartment

Elaine and her mother, Fumiko, in Fumiko and Yayeko's apartment.

“…she’s been living there for 59 years…When they first moved to Chicago they lived around Beldon and Clark. And then…my uncle bought a five-flat apartment building on Cornelia [Street] and for many years the three siblings each had an apartment in this building. My uncle eventually married and moved into a home in Roselle. But my mom and my aunt still live in that building.”

Fumiko (left) and her older sister Yayeko have lived together in the same building for 59 years.

Elaine, Josh, Sam, and Fumiko cook a meal together in Fumiko's apartment.

“...she [Fumiko, Sam’s grandmother] was around a lot watching me and my brother because my mom would be at work until later. We’d get off of school and she’d take care of us. I think some of my biggest memories or times I think about the most…is cooking. For New Years we do a big, giant celebration…that is mainly based around food…traditional Japanese food… it was my grandma and her sister that would do most of the cooking in the past but now that they’ve gotten older they can’t do so much. So it’s fallen onto the newer generation…the past few years I’ve only made it back for maybe one or two New Years, but I like to help with a lot of the prepping as much as I can.”

Sam and his grandmother, Fumiko.

“My grandma, my strong memories of her are her working into her mid-80’s full time. I don’t recall the company…it was a jewelry company, she was…the assistant to the…CEO. But I just remember never seeing her drive when my grandpa was around and then when he passed away she just picked up right where he left off. She stepped up…She’s the reason I came home, basically. Every time we would say goodbye and they [Fumiko and his Great Aunt Yayeko] would cry, like they thought it would be the last. It just kind of broke my heart. I lived out of the city for the last seven years, so I decided to come back for her, for family.”

Josh and his grandmother, Fumiko.

The Questions

1) What would you ask the original owners of these objects, if you could speak to them today?

Fumiko, Elaine's mother.

“One thing that I’ve wondered is, when my mother’s family was on this train for four days and the windows were covered and they didn’t know where they were going: what did they think? I want to know what she was thinking. What thoughts were in her head? I wondered…we look at this in hindsight, we knew that they were there [in the incarceration camp] for three years. When they were there, they had no idea when it was going to end, if it was going to end…and so I would like to know what their thoughts were during this time.”

Sam wearing his grandfather's gi.

“I guess pertaining to the army jacket, I find that pretty interesting. I’ve heard a lot of stories, and people have made documentaries…about Japanese-Americans enlisting in the army after being interned in camps. So I guess if I could ask my grandpa about that, I would just ask what his feelings were towards his government and if he enlisted…if it was mainly just about showing loyalty to the United States…whether it was something he really wanted to do, or if it was something he had to do?

[Sam mentions the gi]. “It’s been a long time since I’ve done Judo, so I guess it would have been cool just to practice that with him. I don’t think I actually ever got to do that [with him].”

“Well, I think the army jacket is really significant because it was such a controversial decision during the time: to join the army when your family and you are being incarcerated, and your rights are being denied as Americans, yet you’re being asked to prove your loyalty to a country that denies you your civil rights and denied your family [its] civil rights, has called you alien and told you can’t own land, and taken away all of your money… And so to join the army and to fight for this country is something I’d definitely want to know more about from my grandpa.”

2) What lessons or ideas do these objects communicate that you hope your children/ future children will carry through their lives?

Akira's US Army photograph, signed by him with "Love."

“It would probably go back to the story of our family being interned and how they dealt with that, how they reacted to it…They did the best they could with the circumstances they were given. I don’t think and they ever really had feelings—or at least what I’ve taken away from it—they aren’t really angry about it, and they’ve learned from it. It’s made them who they are… you don’t see yourself as a victim necessarily. Despite what the country might think of you, or how it treats you, you still act a certain way, and that way is just being a good, model citizen. You try to prove them otherwise.”

“Well from the gi, I think I would take respect and commitment and discipline…From the army jacket I think humility and humanity, and the dangers of humanity, and the need to be in solidarity with minorities and to stand up against injustice. And to remember the history of our family.”

“I want to say so much, but I have one thought and that is: that you can suffer injustice and you can still go on to live your life without bitterness or resentment.”